In a shift from the norm, California homeowners can now transition from renting out Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) – commonly known as “granny flats” – to selling them in the style of condominiums, thanks to the newly passed Assembly Bill 1033.

Spanning a range of styles from converted garages to tiny standalone homes in backyards or even unused sections of a primary house, ADUs have been a significant part of California’s housing landscape. This legislative move, introduced by Assemblyman Phil Ting from San Francisco, aims to foster homeownership opportunities.

For this system to come into play, however, local governments must actively choose to adopt the ADU-as-condominium model.

Here’s a breakdown of how it operates in cities that embrace this initiative:

- Utility Notification: As with any new condo establishment, those constructing ADUs must inform local utility providers, which includes services such as water, gas, electricity, and sewerage.

- Formation of a Homeowners Association (HOA): A necessary step to assess dues covering communal areas like shared driveways, pools, or rooftops.

- Separate Property Taxation: The primary residence and the ADU will each have distinct property taxes.

Ting anticipates that, at least initially, these ADUs will predominantly be sold to close acquaintances or family of the property owners. However, as this trend gains traction, the scope of selling ADUs could soon mirror standard real estate practices.

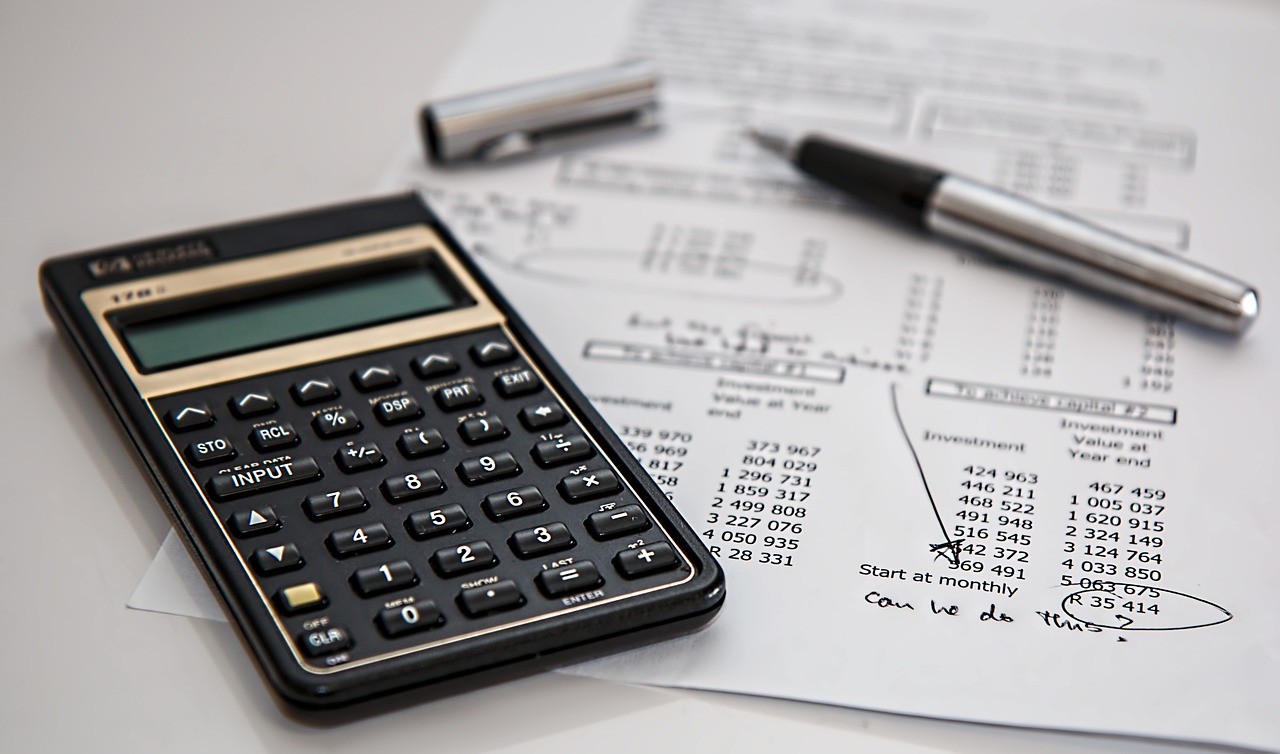

Meredith Stowers, an ADU-focused loan officer at CrossCountry Mortgage in San Diego, perceives this as a win-win situation for existing homeowners and potential new buyers. She notes that many homeowners, especially retirees on limited incomes, can utilize this to bolster their financial status. Not only does it provide retirees an avenue to maximize the equity of their property, but it also presents younger families with a feasible entry point into the housing market.

Highlighting a prevalent dilemma, Stowers explained that many retirees find it economically unsound to relocate to a smaller residence after years of accruing high-rate loan modifications. But this legislation offers them a novel solution: construct an ADU, move into it, and potentially put their primary house up for sale.

Such an approach to ADUs isn’t unprecedented. In 2019, after deregulating ADU construction constraints, Seattle saw a fourfold surge in ADU permits from the previous year. A March report revealed that Seattle granted permits for both attached and detached ADUs, with a noteworthy portion being multi-ADU sites or new single-family property developments.

In Seattle, for example, detached ADUs or “backyard cottages” spanning over 1,000 square feet were reportedly sold for figures ranging from $500,000 to $800,000.

This progression, mirrored in other states like Oregon and Texas, signifies a promising direction for California’s housing landscape, potentially revolutionizing how homeowners and buyers perceive and deal with ADUs.