Image credit: Unsplash

On Monday the 12th, a 4.4 magnitude earthquake struck the Los Angeles area, hitting a lesser-known but potentially significant fault system: the Puente Hills thrust fault. Experts have pointed to the similarities to the well-known San Andreas fault that runs along the outskirts of the city, but the Puente Hills fault lies directly beneath some of the most densely populated places in the Los Angeles and Orange counties, including the heart of downtown Los Angeles. The fault could one day produce a massive earthquake, say experts, warning of a magnitude as high as 7.5.

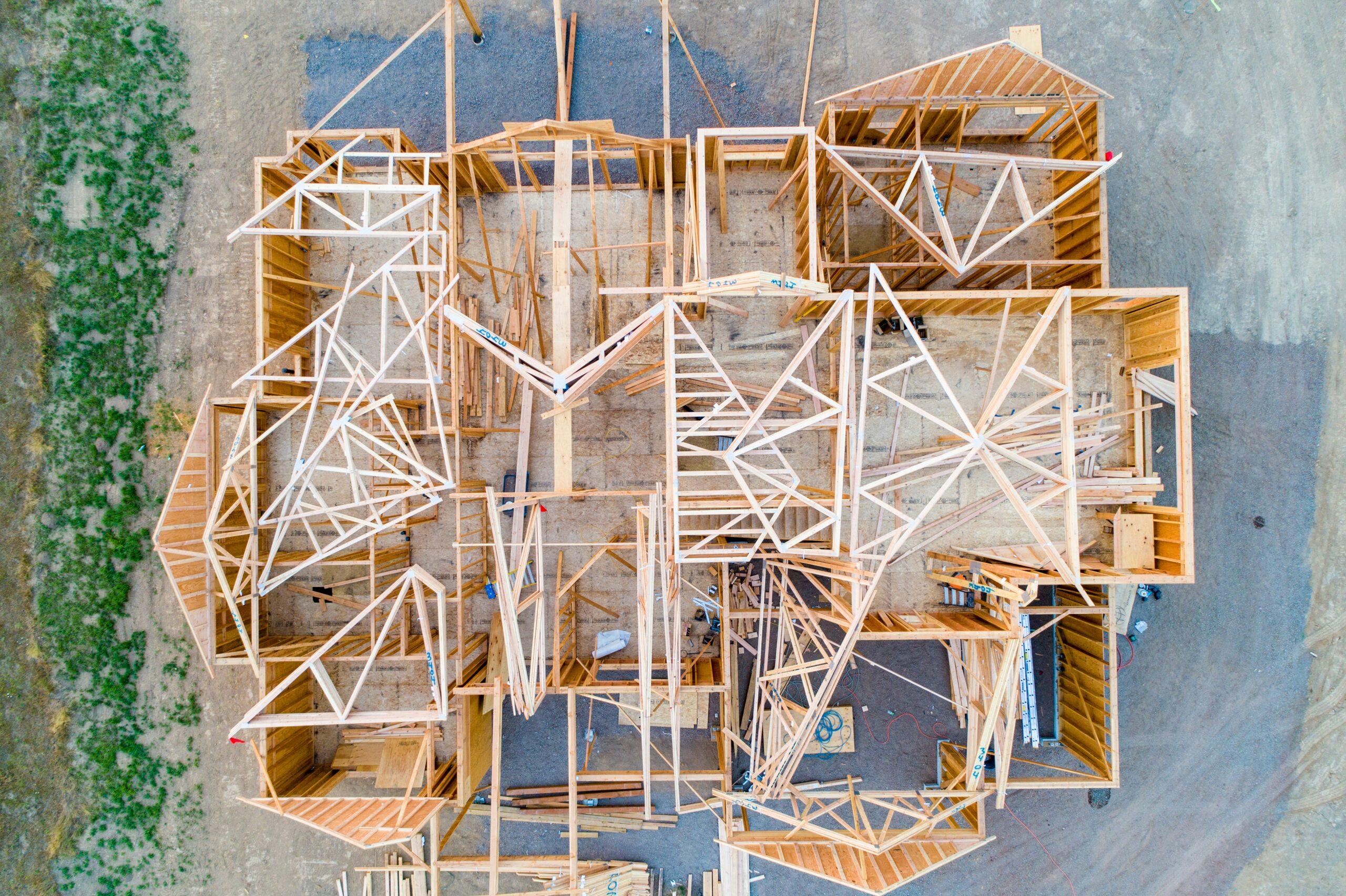

The Vulnerable Underbelly of Los Angeles

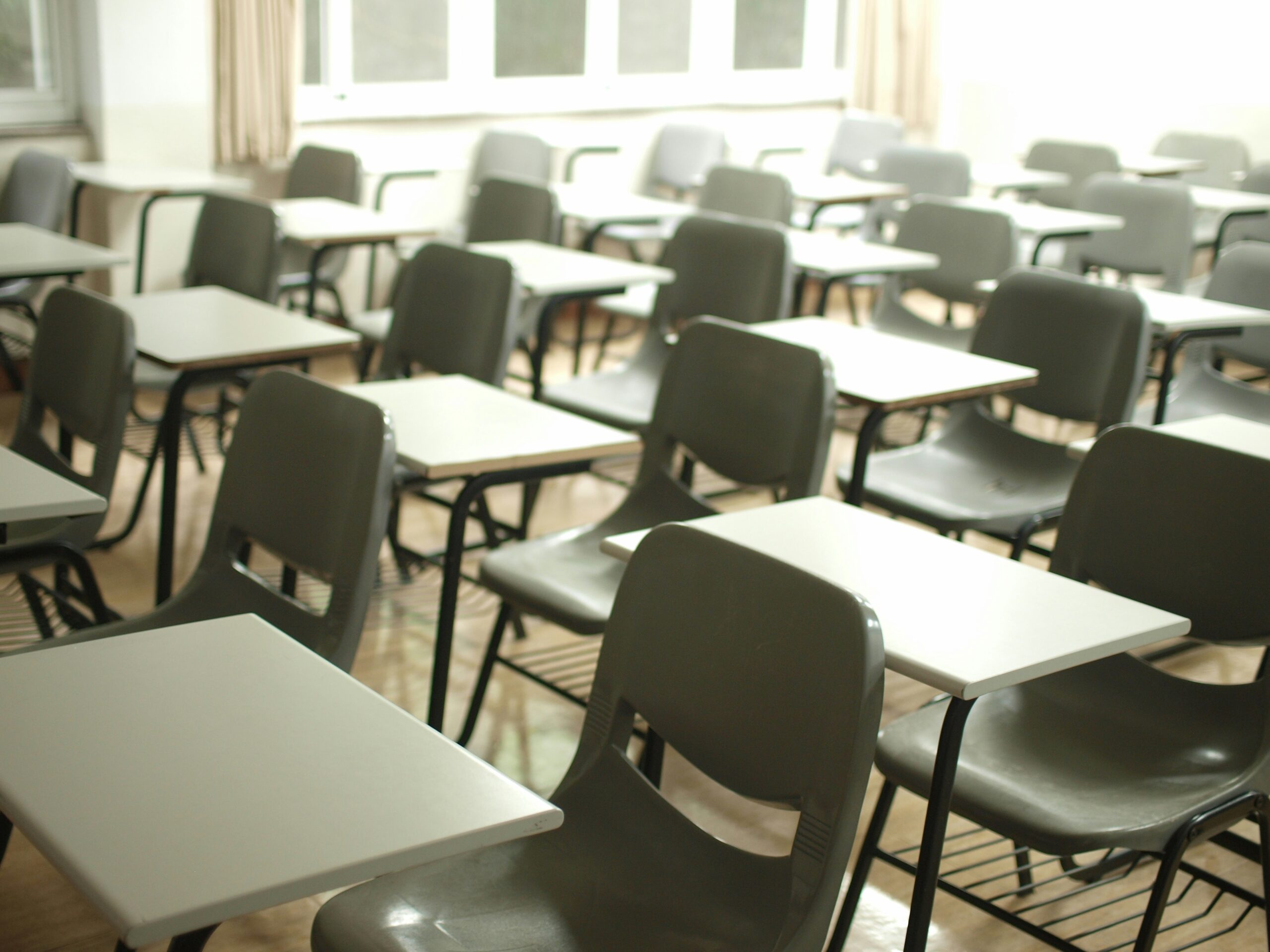

“We have an incredibly dense concentration of vulnerable buildings right on top of the Puente Hills fault, so that’s what makes it so particularly dangerous,” said Lucy Jones, a seismologist and a research associate at Caltech. Many of the structures on top of the fault were built in the 1950s and 60s and have yet to be retrofitted to meet modern seismic safety standards. The unreinforced concrete common in these buildings poses a particular risk in predictive earthquake models, as their likely collapse will have a more significant fallout.

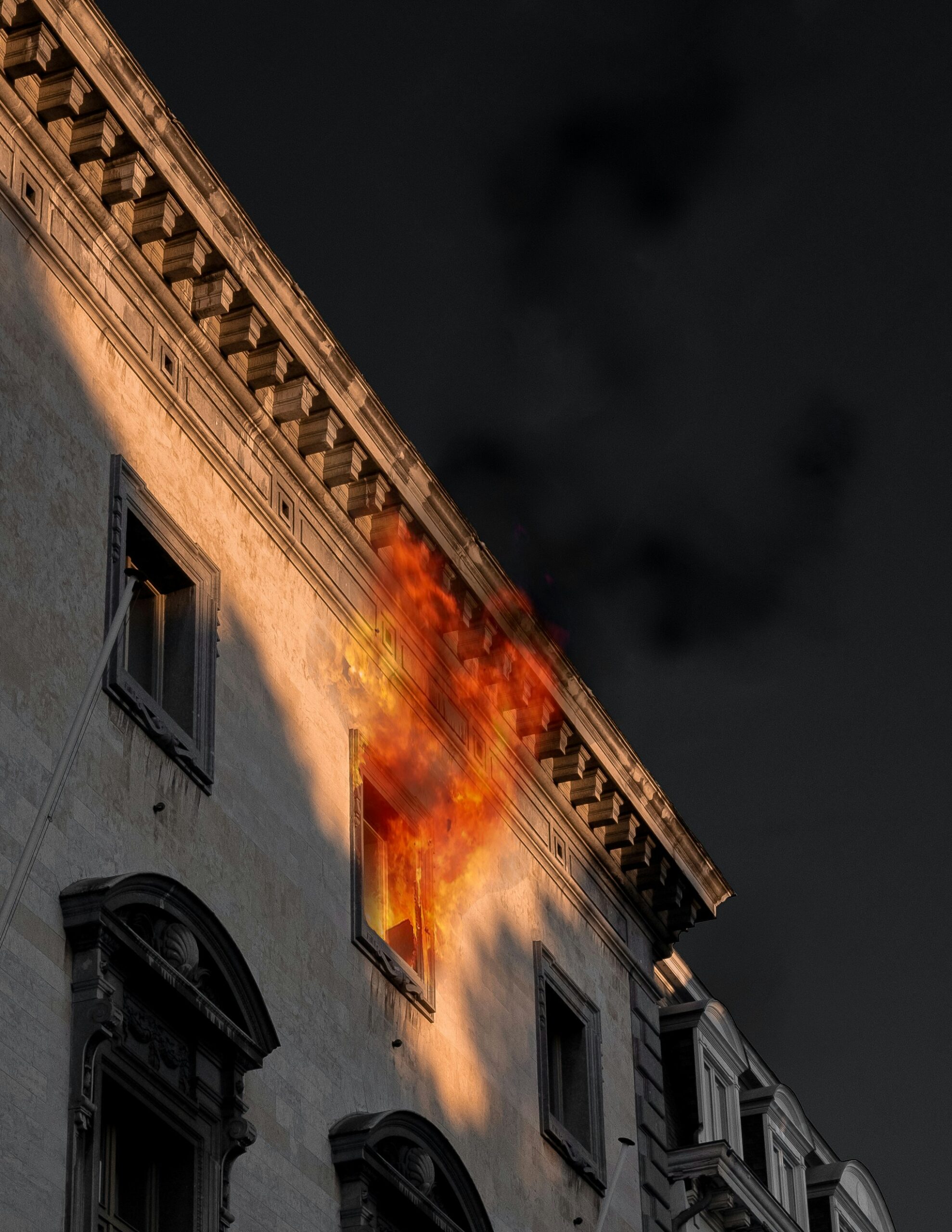

“Concrete is heavy,” Jones said, and went on to say, “When we’ve run these models, those are the buildings that are killing a lot of people.” Some models analyzing a potential 7.5 magnitude earthquake have predicted as many as 18 thousand deaths in the Los Angeles area.

The Complex Problem of the Puente Hills Fault

The Puente Hills fault is one of a complicated series of thrust faults that are described as “blind” because they are hidden beneath layers of rock and sediment. This makes them difficult to predict until they become a problem. This system includes faults that are stacked and oddly inclined, running through the Los Angeles basin. While it isn’t clear that the Puente Hills fault is the specific one responsible for Monday’s quake, experts see it as a top candidate because of its proximity to the epicenter.

Blind thrust faults are notorious for their destructive potential. A similar fault caused the 1994 Northridge quake, a magnitude 6.7 event that caused widespread damage across Los Angeles. An earlier quake, the 1987 Whittier Narrows quake, hit just a branch of the Puente Hills fault and registered a magnitude of 5.9. That earthquake killed eight people and caused $358 million in property damage.

Puente Hills vs. San Andreas: Disasters Waiting to Happen

Southern California, and Los Angeles in particular, is built atop a seismically active landscape full of active fault lines. The Puente Hills and San Andreas faults are only two of these faults, but they carry disproportionate potential for destruction.

The San Andreas fault is one of the largest and most active faults in the world and is regularly responsible for some of California’s most significant earthquakes. It runs from the Southern California desert to Northern California’s coast and is the main plate boundary between the Pacific and North American plates. It is capable of causing large quakes that span great distances. But its last truly major event was the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake, retroactively estimated to have been a 7.9 magnitude quake that caused significant damage. The area had been only sparsely populated at the time.

“Summed up over the next few thousand years, the San Andreas is going to do more to us than the Puente Hills,” says Jones, though this is “because the Puente Hills will move once and the San Andreas is going to move 20 times.”

The Puente Hills fault threatens the Los Angeles Valley with the potential for a single, history-changing cataclysm that would directly strike urban centers. Area seismologists have pointed out that, while Southern California had been relatively quiet in terms of significant quakes over the past two decades, this year has already seen 13 earthquakes of magnitude 4 or greater. “We really are earthquake country,” warns Jones, “And we’ve been lulled into a sense of complacency.”