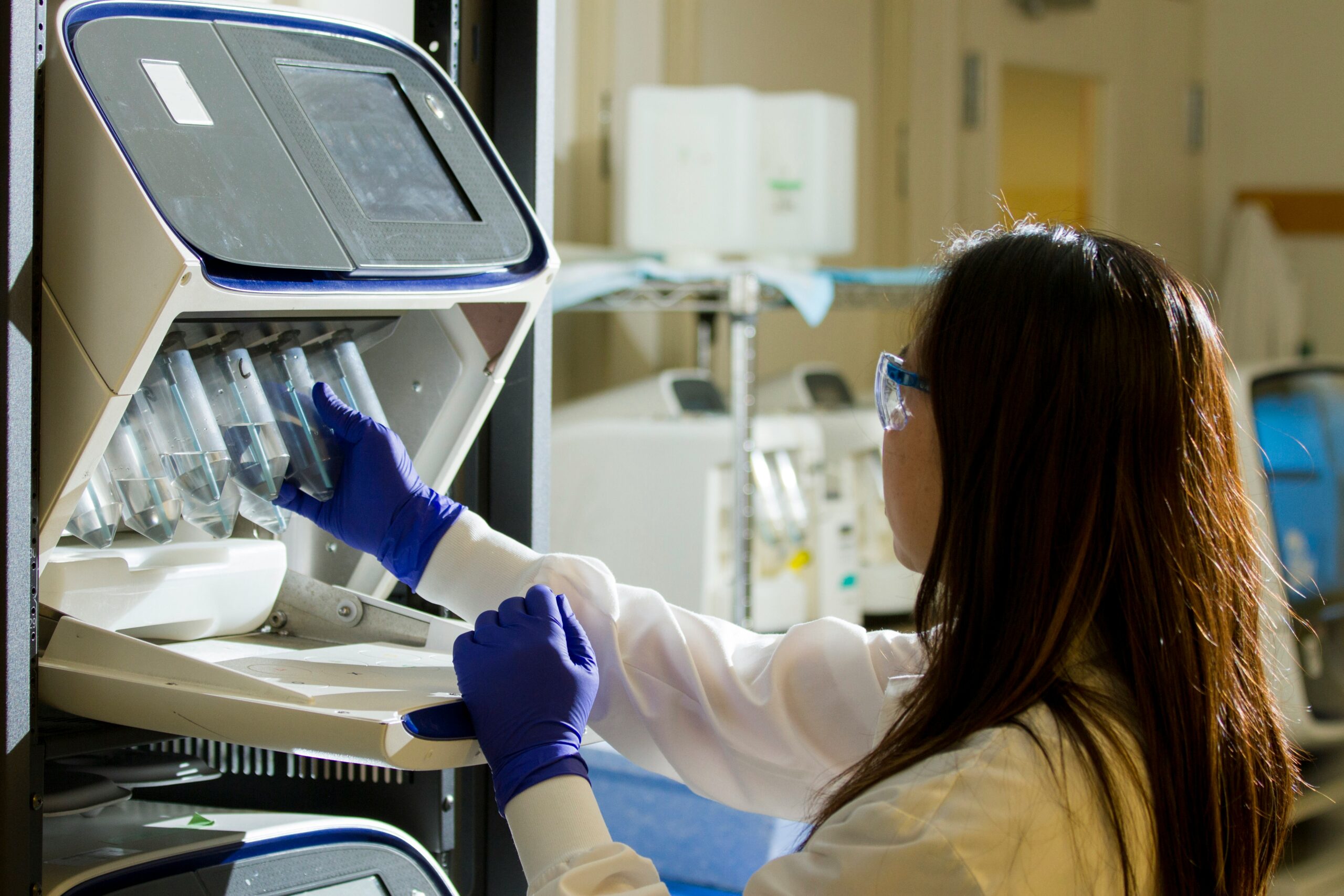

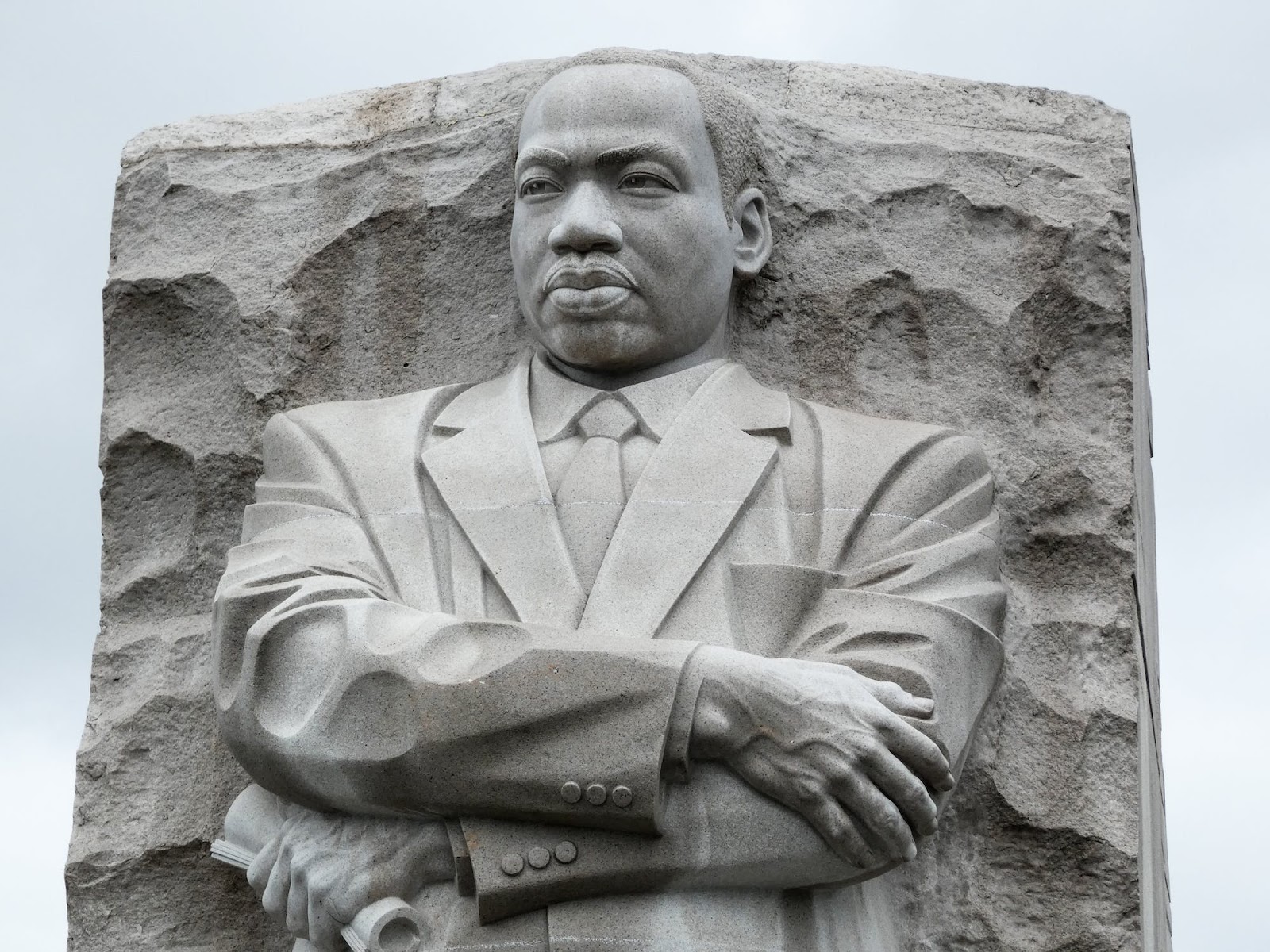

On a quiet afternoon at the Berkeley Martin Luther King Junior Middle School, a group of elementary students gathers around a long table. Dish soap, yeast, plastic bottles, and some hydrogen peroxide containers are scattered across the surface; materials more likely found in a kitchen than a chemistry lab. At the center of it all is 16-year-old Mia Luh, sleeves rolled up, eyes gleaming with purpose. With a steady hand and a warm smile, she begins guiding the students through a simple chemical reaction, one elephant toothpaste explosion at a time.

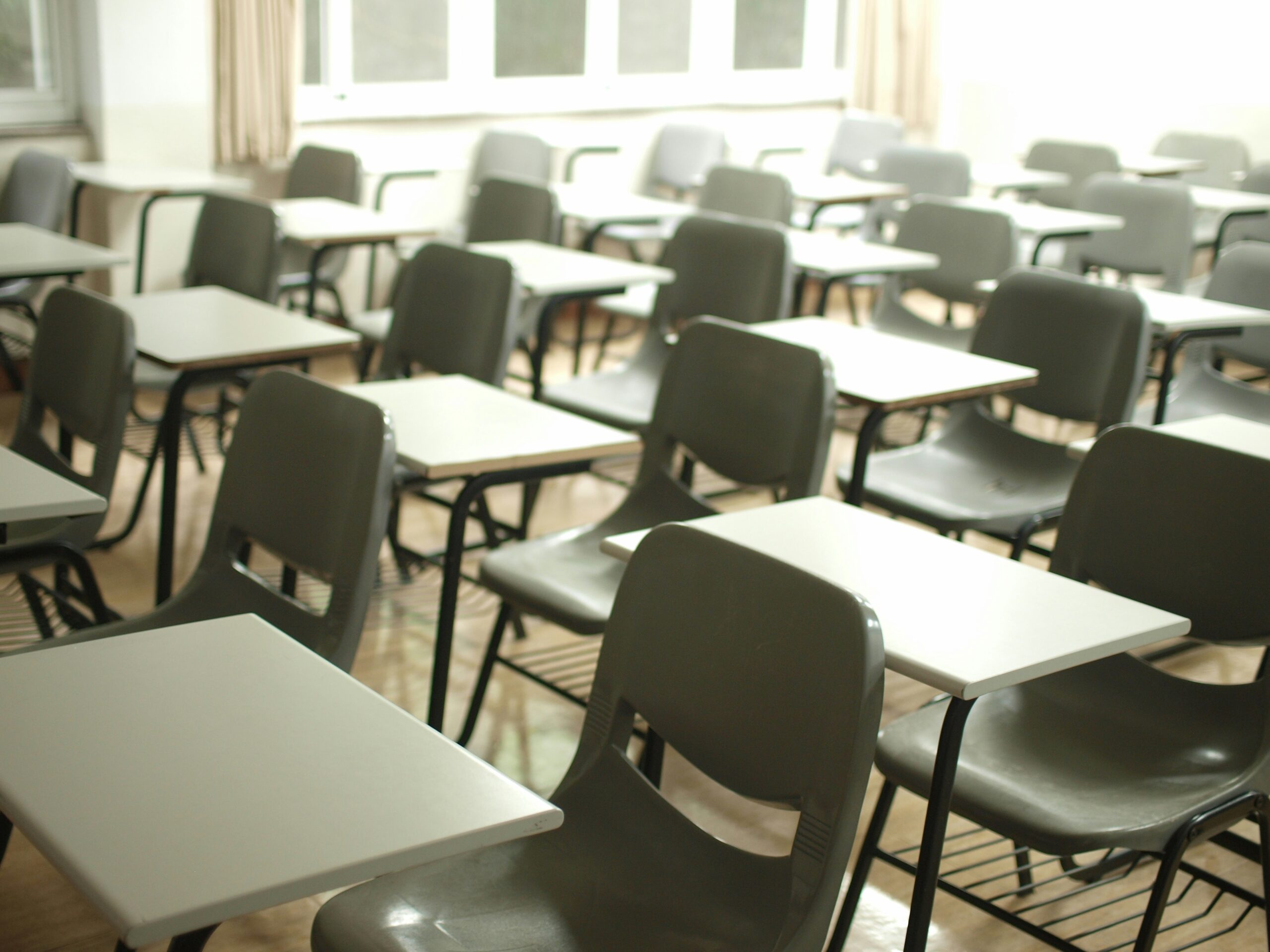

This isn’t just a science demonstration, it’s part of Mia’s grassroots initiative to tackle a systemic gap in public education: the lack of affordable, experiential STEM learning in underfunded schools.

“I grew up with a ‘learn by doing’ approach to science,” Mia explains. “But I realized that many students in Berkeley’s public schools didn’t have that same access either because their schools lacked resources or because science was taught only through textbooks. I wanted to change that.”

What began as a personal observation quickly turned into a bold, community-based project. Mia’s idea was deceptively simple: bring science to students using everyday household items, delivered in community spaces where cost and infrastructure weren’t barriers. No microscopes, no high-tech lab kits, just curiosity, creativity, and connection.

While many STEM initiatives rely on expensive equipment or external funding, Mia’s model thrives on accessibility. In her sessions, students might learn about chemical reactions with kitchen ingredients, build circuits with foil and batteries, or explore basic physics using cardboard ramps. These low-cost, high-engagement activities are designed not just to inform, but to ignite.

“Kids light up when they see something they’ve read about actually happen in front of them,” she says. “And when the materials are things they already have at home, it empowers them to keep experimenting on their own.”

But building the program was not without its challenges. As a teenager, Mia had to earn the trust of school administrators and community partners. She reached out to the Berkeley LEARNS after-school program and the public library system, pitching her idea with patience and persistence. Her professionalism and clarity eventually won them over.

“There was some skepticism at first,” Mia admits. “I was just one person, not a nonprofit or formal educator. But once they saw how prepared I was—and how excited the kids were to participate—they really got on board.”

Each session is carefully structured to be age-appropriate and engaging. Mia develops her own lesson plans, often tailoring them based on the needs of the group. She’s found particular success with interactive storytelling—framing scientific concepts within narratives to help younger students grasp abstract ideas. She also uses Socratic questioning techniques learned through her math tutoring experience to deepen critical thinking.

While her presence currently powers the initiative, Mia’s long-term vision is rooted in sustainability. She’s working on documentation like lesson plans, facilitator guides, materials lists that will allow teachers and volunteers with low resources to carry the program forward after she graduates.

“I don’t expect the project to survive in its current form without me,” she says. “But I hope it inspires others, especially educators, to see what’s possible with a little creativity and intention.”

Already, she’s seeing signs of impact. Some teachers have begun replicating her activities in their own classrooms. Parents report that their children are talking about science in new ways at home. And students, once disengaged, are now asking when the next session will be.

What sets Mia’s work apart is not just the innovation of the model, but the clarity of her purpose. In a world where educational inequality often feels overwhelming, she’s found a way to chip away at the problem, one vinegar volcano at a time.

Back at the school campus, the hydrogen peroxide that is usually lying dormant in first aid kits at home is bubbling up rapidly, prompting a round of giggles and gasps from the students. Mia claps along with them, then dives into an explanation of carbon dioxide and chemical change. The room hums with energy, not from any high-tech device, but from the sheer joy of discovery.

And that, for Mia, is the whole point.

Written in partnership with Tom White