Image credit: Unsplash

Near the close of their speeches at the Democratic National Convention, both Michelle and Barack Obama exhorted their listeners to actively support the Harris campaign, to “work like our lives depend on it.” Former President Obama declared, “If we each do our part over the next 77 days, if we knock on doors, if we make phone calls, if we talk to our friends, if we listen to our neighbors . . . we will elect Kamala Harris as the next President of the United States.” “Do something,” asked the former First Lady, “you know what you need to do.”

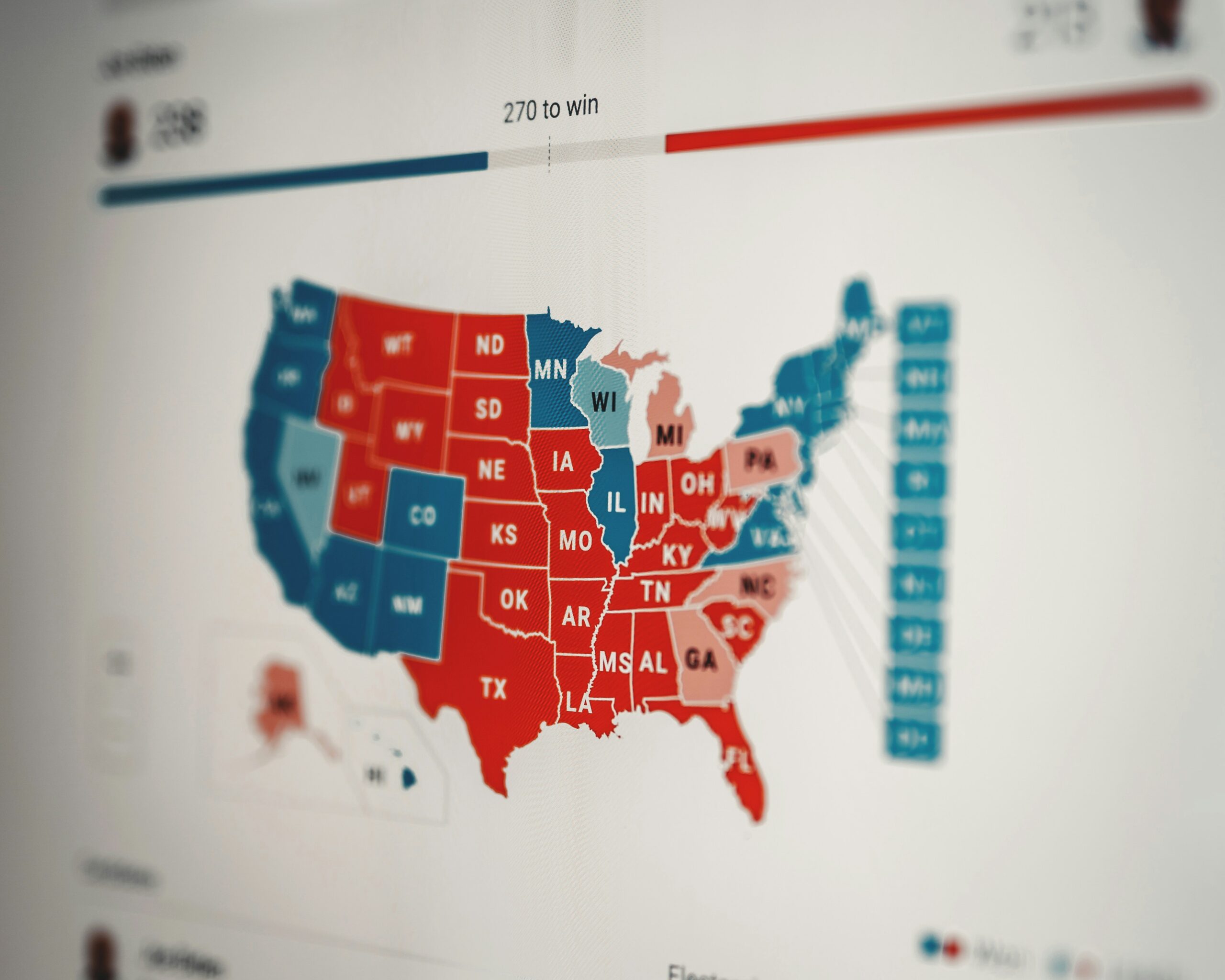

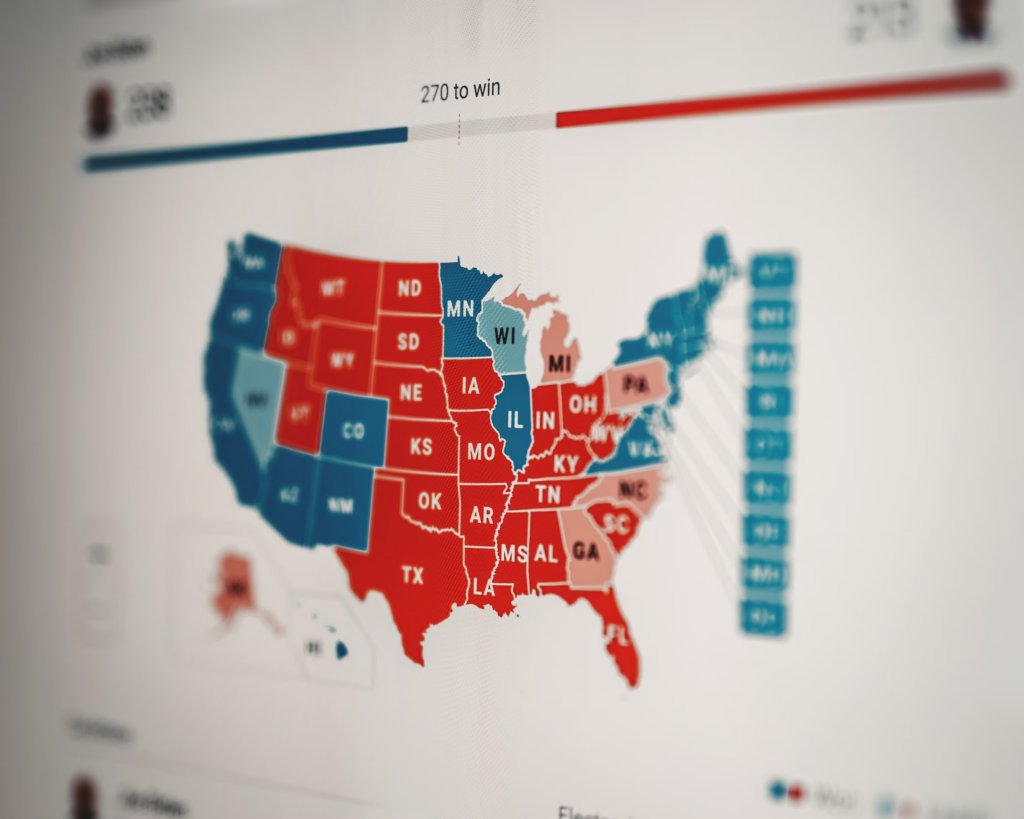

But there was and is a problem with the Obamas’ urgent call to action: the roughly 80 percent of the population who do not live in “swing states” lack a clear notion of what they “need to do” to actively support their candidates. In those “sure states” (as they once were labeled), there is little to be gained, for either Democrats or Republicans, in knocking on doors, conversing with neighbors, calling people in nearby towns and cities, or putting up yard signs. The few steps that non-swing state citizens can take – writing checks or joining a phone bank to cold call swing state voters – offer little of the satisfaction or sense of solidarity that can come from in-person participation in a political cause.

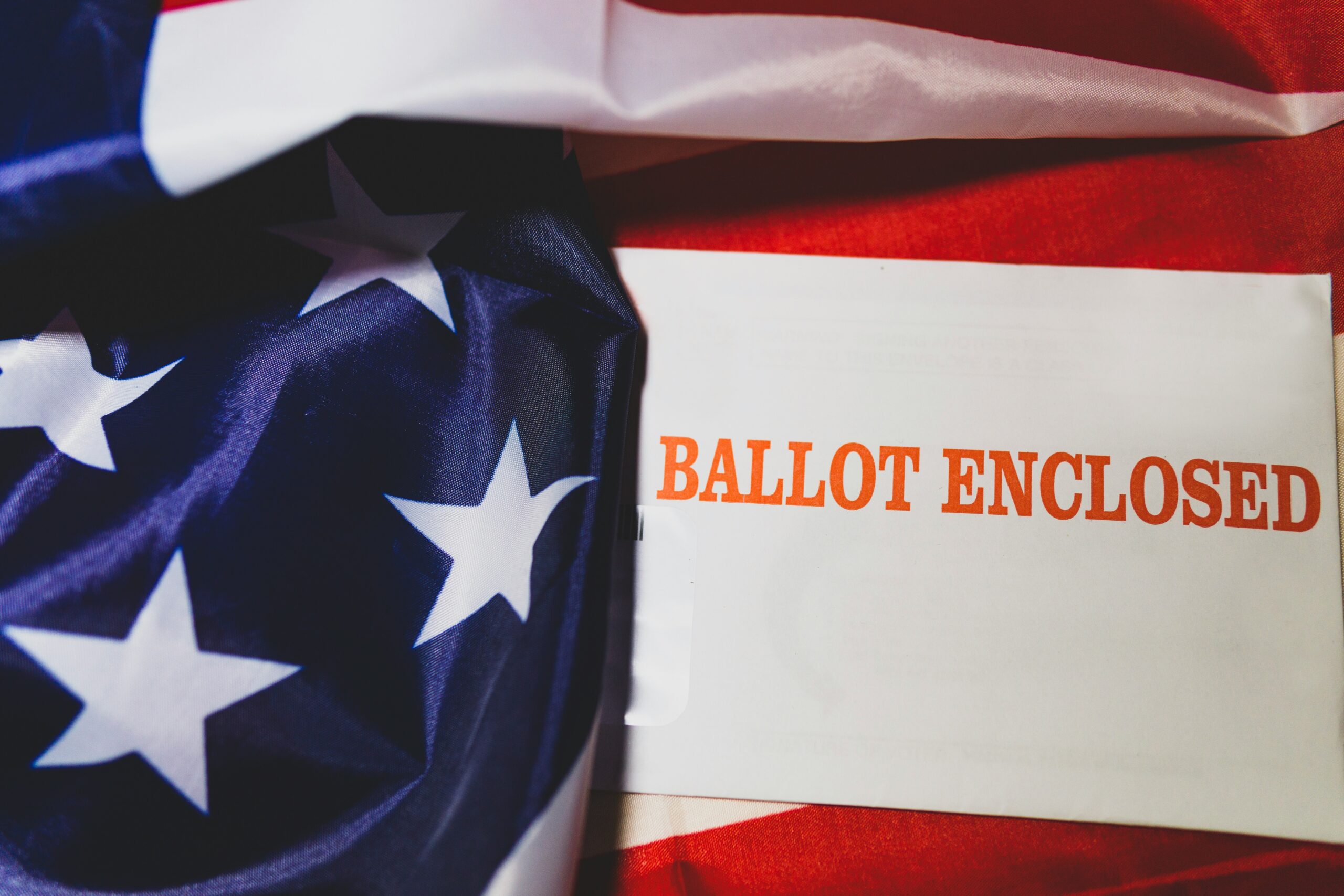

The reason for this, of course, is our deeply flawed electoral system, in particular the practice in 48 states of awarding all of a state’s electoral votes to the candidate who wins that state’s popular vote. That practice sequesters most of us, deterring us from becoming fully active, from learning by engaging our fellow citizens and participating in the processes of democracy. Both political parties insist that this is the most important election of our lifetimes, but most Americans are mere spectators, sitting in front of screens watching the campaign unfold in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Georgia, or Arizona.

“Winner take all” (WTA) also makes it more likely that the candidate who loses the popular vote can still win the electoral vote and become President – an outcome that violates basic democratic principles. Moreover, the system depresses voter turnout and leads to the quadrennial emphasis on issues that matter most to swing states – not to mention the extra monies that tend to flow to swing states between elections.

Why do we have this system? It’s not mandated by the Constitution. The framers left it to the states to decide how to allocate electoral votes, although most of them appear to have expected the states to adopt district-based systems. For the first decade or so, many states did allocate electoral votes by district (often congressional districts), while others deployed WTA (then called the “general ticket”) or allowed their legislatures to choose electors without even holding a popular election. WTA then took root in more states for largely partisan reasons: political majorities in individual states wanted to guarantee that their candidate would win all of the state’s electoral votes. Virginia famously took this step in the hotly contested election of 1800 to prevent John Adams from winning even a few electoral votes. The shift was so unprincipled that Virginian John Marshall, on the brink of becoming Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, declared that he would never vote for President again while WTA remained in place.

Indeed, WTA was widely disparaged throughout the early decades of our history. Four times between 1813 and 1826, the Senate approved constitutional amendments to require district elections; on one occasion the House fell only a few votes short of the required two-thirds vote that would have sent the amendment to the states to be ratified. Some of the Constitution’s framers themselves, including James Madison, favored prohibition of WTA. North Carolina Representative James Strudwick Smith argued that a district system would “give the minority as well as the majority of the people of every state a chance of being heard. . . . You will bring the election near to the people and consequently you will make them place more value on the elective franchise.”

Efforts to eliminate WTA have recurred for the last two centuries. Michigan adopted a district system in the 1890s, as Maine and Nebraska have done more recently; Republicans and Democrats in numerous states have seriously considered taking that bold step in both the 20th and 21st centuries. Meanwhile, Congress periodically debated amending the Constitution to require the allocation of electoral votes either by districts or through a proportional system in which a candidate’s electoral vote would match their percentage of the popular vote. In 1950, the Senate approved an amendment calling for a proportional system; in 1969, the House passed an amendment that would have replaced the Electoral College with a national popular vote – which also, of course, would have eliminated WTA.

The historical record thus makes clear that widespread dissatisfaction with WTA is not a modern phenomenon: it is as venerable as the Constitution itself. Reform efforts nonetheless have met with limited success, thanks to the primacy of ever-shifting partisan interests that overrode democratic values or beliefs about how a presidential election should work. It is difficult to conjure up a principled rationale for an electoral system that not only discards the votes of political minorities but effectively adds them to the winner’s total.

Can anything be done? Individual states could join Nebraska and Maine in adopting systems that better suit the political diversity of their populations. But history suggests that such a strategy will not get very far. Parties with reliable majorities in each state have had little interest in diminishing the electoral payoff that comes with winning the state; and politicians of both parties have been reluctant to reduce their states’ Electoral College influence by acting as first movers, however principled such a decision might be. California will not abandon WTA while Texas retains it. And ongoing efforts to adopt the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which would require participating states to award all of their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner, face difficult hurdles.

The more plausible, and durable, strategy would be a constitutional amendment requiring states to allocate their electoral votes utilizing some type of proportional scheme. Alternatively, a constitutional amendment providing for a national popular vote would achieve the same result. (Despite their success in Maine and Nebraska, district systems will remain problematic as long as partisan gerrymandering is widespread and legal.) Constitutional reform that modifies or replaces the Electoral College would also provide an opportunity to rid ourselves of the deeply undemocratic – and hazardous – “contingent” election system. Currently, if no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes, the House of Representatives selects the President, with each state’s delegation (no matter how large or small) casting one vote. Although not utilized since 1824, the contingent system – which has the rare distinction of having been denounced by both Thomas Jefferson and Mitch McConnell – is a ticking bomb, set to explode during a close election.

The task of Electoral College reform is daunting. Since the 1970s, the mere mention of reform has often elicited responses of weary pessimism even among those who favor the idea. Our Constitution is notoriously difficult to amend, and Republicans reflexively oppose reform because they currently believe that the Electoral College works in their favor. The polarization and inflammatory rhetoric of contemporary politics make cooperation, and even discussion, difficult.

But that does not mean we should continue to accept an undemocratic system that was created more than 200 years ago, itself a product of partisanship and gamesmanship. Since the 1940s (when the first reliable polls were taken), a majority of the American people has favored Electoral College reform or abolition; we have come close to altering the system on multiple occasions; and partisan perceptions of advantage have commonly shifted over time. Change will be hard but not impossible.

No reform will happen between now and November; voters will focus on more immediate issues through Election Day and likely into January. But no matter the outcome of this year’s election, the challenges facing American democracy will persist, and among them is the task of doing something about a presidential election system that dampens engagement and turnout, deforms the conduct of campaigns, and fails to match democratic values. Surely we can do better – and have a national conversation about how to do so. Just imagine how very different the current campaign would look if every vote, in every state, really did count.

Written in partnership with Alex Keyssar and Elizabeth Cavanagh.